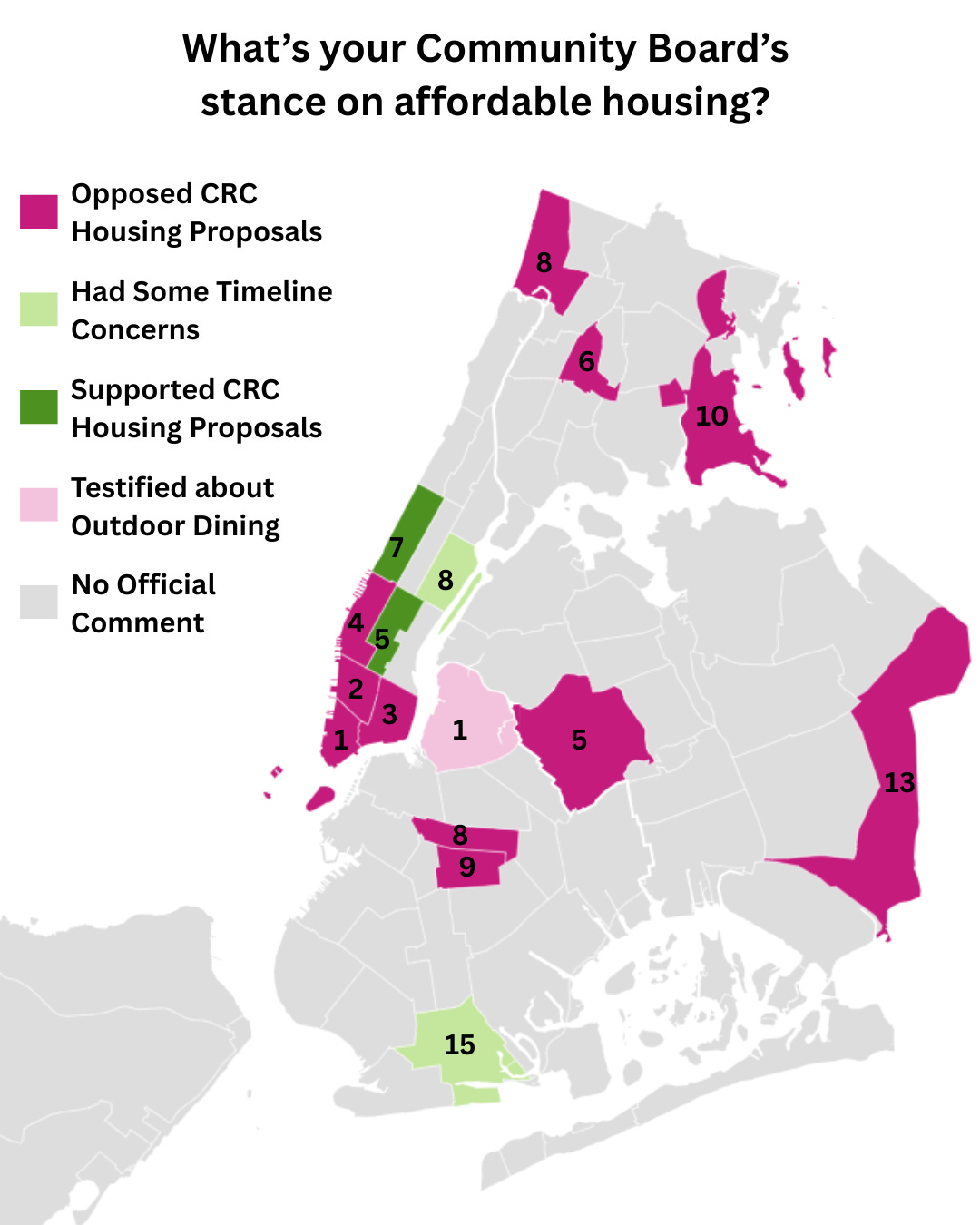

What’s your Community Board’s stance on affordable housing?

And actions you take if your board isn’t representing your values

You’ve heard that New York City is in a housing crisis. You’ve also heard that there are New Yorkers out there saying, “We support affordable housing… just not here.” But is that just other neighborhoods- or is your community board doing the same?

Community boards, NYC’s hyperlocal advisory bodies, are meant to be the voice of the community. They have no legislative authority, but they weigh in on neighborhood development and can have significant influence on what gets built and how. Is your community board representing your neighborhood well? What’s your community board’s take on affordable housing in your neighborhood?

Community boards are known for being older, whiter, and more homeowner than the rest of their area. They’re also known for blocking new development. I wanted to see what community boards thought of the opportunity to change the city charter to streamline affordable housing production. Here’s what I found, and how your community board weighed in (if at all).

What are these housing proposals again?

This year, New York City convened a Charter Revision Commission (CRC): a temporary body tasked with reviewing and suggesting changes to the city’s founding document, the City Charter. The commission focused on reforms that would increase housing affordability. The proposals they’ve drafted will appear on the November 2025 ballot, where voters will decide whether to adopt them. An aside: I think all the proposals are thoughtful and we should get them passed.

While shaping the policy proposals, the commission held public hearings and opened the door for input from residents, organizations, and government bodies- including community boards.

Why do community boards care?

Community boards weren’t required to weigh in. But many did, in part because several of the proposed changes directly impact them: especially those related to land use procedures, how quickly they must respond to new building applications, and how much influence they retain in planning decisions. These proposals strike at the core of what community boards do- they’re the voice of the community in whether and how something gets built. They’re meant to provide feedback from a neighborhood perspective, and present local wisdom as the ones who live and work on the blocks most affected by a new development. In practice though, their participation can make building projects more expensive to execute or even impossible to pencil, actually leading to less affordable housing overall.

Since they weren’t required to provide input, only 16 of the city’s 59 boards submitted formal testimony to the commission- some with thoughtful recommendations, others with fiery language, and many airing out how they really feel about new development.

Here’s what I found.

Out of NYC’s 59 community boards:

11 submitted formal testimony opposing the proposals.

2 raised concerns about timeline and process, and the commission integrated their feedback so I think they should be supportive of the end result.

2 were supportive overall.

1 wrote in about outdoor dining instead of housing🤷

A few themes emerged in how community boards framed their concerns- and what they revealed about their values around affordable housing and their own power.

Theme #1: Attacking the commission for being a conspiracy by authoritarians, elites, and lobbyists.

These kinds of extreme statements weren’t the norm- but they weren’t isolated either. A couple community board statements veered into full-on skepticism of the process itself. Bronx Community Board 8 accused the commission of attempting to "circumvent and silence" community boards. Only a few community boards were this explicit about deeply mistrusting city leadership. But most community board statements subtly reflected the (perhaps natural) tension between community boards and city institutions.

Theme #2: Standard NIMBY: “We love affordable housing. Just not here.”

There were more community board statements along this familiar line. For example:

“Brooklyn Community Board 9 recognizes that the city as a whole needs to continue residential development to provide sufficient housing for expected future population but treasures our stable and affordable residential community and our historic built context.”

“It is essential to preserve neighborhood character with any housing applications. People purchased homes in lower density communities because they do not want to be in overly crowded conditions.” - Queens Community Board 5

These kinds of statements illustrate a core tension: many boards say they support affordable housing in theory, but balk at proposals that might change zoning or introduce new housing types to their own neighborhoods. It’s a classic NIMBY pattern- supporting affordability only if it doesn’t disrupt the status quo.

Importantly, the commission kept language about neighborhood character in the proposals. In the proposal, to get zoning relief, a developer would need to show that their project fits in with the neighborhood’s character and helps create affordable housing. This neighborhood character test already comes up in other similar decisions, and it’s meant to make sure any new building doesn’t feel totally out of place.

Theme #3: Strategic Push to Preserve Community Board Power

One proposal in the charter revision package would weaken “member deference”: the informal but powerful City Council tradition that allows the local Council member to effectively veto or shape land use proposals in their district. Member deference gives a single Council member the final say on building decisions in their district- and since their political survival depends on keeping local voters happy, they’re often inclined to side with the community board and nearby residents who are most affected by a project. City Council districts are small, so community board pressure carries real weight. Weakening member deference would mean weakening community board influence over the end decision.

And several boards acknowledged that in their statements to the commission. Manhattan CB2 called member deference a way to ensure “local concerns are recognized and protected.” Manhattan CB3 was even more direct, saying it was “adamant” about preserving what little influence community boards already have, and decreasing member deference would “dilute” that power. Bronx CB10 warned that removing these checks would allow affordable developments to be fast-tracked without the community's ability to negotiate.

It’s true, and that’s the point of the proposal. When community boards influence their city council member to demand more concessions from developers, that raises the cost of building in the city. When community boards signal their disfavor for a project, that also opens the door for city council members to kill affordable housing projects or make them more expensive for developers to execute.

While member deference gives community boards more influence over building projects, that influence often works to slow or block new development. If we’re serious about solving the housing crisis, we need to be willing to limit that kind of hyperlocal control when it stands in the way of building more affordable homes.

Importantly, the charter proposals would only apply this change to projects that include affordable housing- keeping member deference for projects that are market-rate only.

Theme #4: Concerns About Shortening the Review Timeline

The vast majority of community boards expressed concern about any policy that would decrease the amount of time that community boards get for review. Today, the community board has 60 days to get feedback from the community and vote on their official opinion (approve/deny). If they don’t produce an opinion during that 60-day timeframe, the process keeps moving without them- it’s a hard deadline.

Here’s what community board review can look like and why community boards want at least 60 days for it:

A proposal for a new building or rezoning is submitted to the community board.

A committee holds a meeting where the applicant presents, members ask questions, and the public may comment.

For complex cases, a consultant might present additional analysis.

The committee invites more public testimony, drafts a resolution, and votes on whether to recommend approval.

The full board reviews and votes on the resolution.

It’s a delicate balance: community boards need time for all these tasks, and yet the need for affordable housing is undeniable. The commission proposals keep the community board review timeline the same: 60 days.

Theme #5: Signs of Progress: A Few Boards Lead on Housing

While most community boards pushed back on the proposals, a few took a more constructive, pro-housing stance. Manhattan CB5 acknowledged that affordability is the district’s most urgent issue and that streamlining the land use process could help address it.

Manhattan CB7 went even further. They recommended expanding the fast-track to include a broader range of projects- like those with at least 10% affordable housing, regardless of financing source (some projects in the current proposal must be publicly financed in order to qualify for the fast track). CB7 also suggested fast-tracking some developments on city-owned land. They also pointed out a crucial procedural flaw: that every player in the land use process has a deadline except the Department of City Planning. They suggested setting a timeline for the agency too- at least for affordable housing projects.

Yes, you heard that right: this community board advocated for the commission to go further than the current proposals. It happens so rarely, one might forget that community boards aren’t limited to just “yes/no”, they can say “Yes, AND”. CB7 serves as an exemplar of what’s possible: not just defending their own power and the status quo, but advocating for more powerful solutions to the city’s housing crisis.

Does your community board reflect your values around affordable housing?

I live in Brooklyn CB9, which landed in the standard NIMBY camp, so my community board isn’t reflecting my values well.

If you’re in the same boat, here are some ways to get involved- from smallest lift to biggest:

Subscribe to your community board’s newsletter and speak up when there’s a project you care about. (Small effort)

Grab coffee with a community board member. Think of this as lobbying, but more fun because you’re getting to know engaged neighbors in your community😊. Community board websites list their members. See if you already know any of them, find out if you’re second-degree connections on LinkedIn, or just reach out to the Chair. Ask to grab coffee as an interested neighbor– you just want to learn more about the community board and how you can make your voice heard. When you meet, let them know you care about housing and want to see more of it in your neighborhood. (Medium effort)

Join a community board committee, like land use or housing. Each community board has a committee related to land use. Being a public member of a committee means you only have to attend one meeting a month, and you get to vote on zoning proposals. Each board has a different process for becoming a public member, but your best bet is to start attending land use committee meetings to demonstrate your interest and email the district manager to ask about their process. (Large effort)

Join your community board. Appointments happen every spring through an application process, but there’s off-cycle appointments too. Sometimes your city council member or borough president can add you to the board off-cycle if you reach out and express interest. Joining my community board in Manhattan was incredibly fulfilling and I learned a ton about how the city works, but it’s a major time commitment to serve on a community board, so it’s definitely not for everyone. (Extra Large effort)

A final note: I found all of the community board statements in the public comment reports from the Charter Revision Commission. You can read the full comments yourself and see exactly what your community board had to say. Click into “Written Testimony (July 15)” or “Written Testimony (June 30)”-- those are the two PDFS that contain the majority of the community board testimony.