Order up: Rezoning with a side of preservation

How landmarks can proliferate as a side effect of rezoning

This is Part 3 of a multi-part series on historic preservation. 🧑🎓🏛️

Wait, what is zoning again? Zoning rules dictate what can be built where. These rules are important because we don’t want factories right next to homes and schools. Sometimes these rules need to evolve with the times though. For example, NYC used to have a ton of garment factories in Midtown South. Now, manufacturing isn’t as common there, so we need to update the zoning for uses that are more relevant now and in the future. Changes to zoning are “rezonings”.

Wait, if rezoning is about evolution and change, then how is this a post about historic preservation?

Usually, rezoning proposals have goals like “making it easier to build X.” X can be affordable housing, taller office buildings, roller coasters; whatever makes sense in a given neighborhood. Historic preservation (what’s historic preservation again?) is not typically the main goal of a rezoning. But, in NYC, historic preservation can happen as a side effect of a rezoning. Why does this happen? And how?

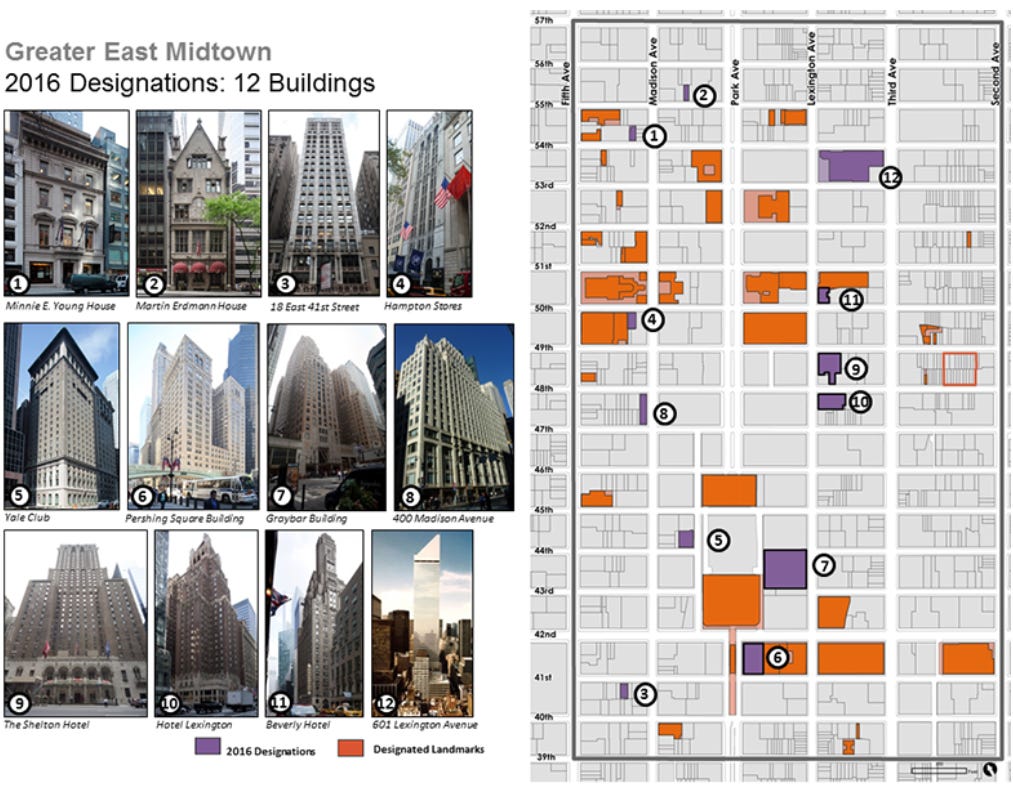

Let’s take one recent example: the 2017 East Midtown rezoning. The goal was to make it easier to build new office space. And 12 new landmarked buildings happened as a side effect. NYC has another rezoning coming up in Midtown South this year. If we look at the East Midtown rezoning as an example, it might give us an idea what the preservationist playbook for Midtown South will look like.

In East Midtown, preservation groups influenced the rezoning

In 2012, the Department of City Planning under Bloomberg proposed rezoning the area around Grand Central in order to make the area more friendly to building new office space. At the time, of the nearly 400 buildings in the area, more than 300 were over 50 years old. Without a change in zoning, the office stock would continue to age, decreasing the competitiveness of the business district and eroding one of the most important job centers and tax bases in the city.

The 2012 proposal died, basically because Bloomberg tried pushing it through very quickly at the end of his last term and without the support of local community boards, preservationists, and the hotel workers union.

So what’s a super common politician move when a policy isn’t quite ready for prime time? Make the policy into a committee instead, and build buy-in to get it passed in another form. So De Blasio commissioned the East Midtown Steering Committee in 2014. The Steering Committee consisted of 10 organizations, distributed roughly evenly across three sets of interests: local Community Boards, business and real estate interests, and preservation and labor organizations. The Steering Committee did not have decision making power– their task was to provide recommendations to inform the administration’s rezoning proposal.

Steering Committee recommends more landmarks, LPC executes

In 2015, the Steering Committee issued their report, recommending that “the Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) should calendar and designate as landmarks as many historic resources as it deems appropriate.”

In response, LPC agency staff surveyed the area and located 12 potential new landmarks. In 2016, the 11 Mayor-appointed commissioners on the LPC unanimously approved all 12 new landmarks. During the hearing, preservation groups attended and gave testimony for each of the 12 buildings. Of the 12 buildings, there were 4 where the building owner was in favor of the designation, 4 where the building owner was against the designation, and 4 where the building owner did not testify so their position is unknown. Only one group testified against landmarking multiple buildings: the Real Estate Board of New York.

The twelve 2016 landmarks brought the total landmarks in the area to 50 buildings. Since LPC does not have a process to de-landmark a building, these buildings will stay protected indefinitely.

What can we learn from the East Midtown rezoning?

In the upcoming Midtown South rezoning, we can expect to see the following preservationist plays in action:

Advocate to community boards and LPC to designate specific buildings

Advocate to electeds and the LPC to review the area to identify additional landmarks

If the above don’t work, try to kill the rezoning

For community board members weighing in on rezonings, three additional takeaways:

Err on the side of flexible zoning. In 2017, CB5 recommended that the East Midtown rezoning discourage residential usage:

“Dozens of properties have an incentive to convert from Class B office space to residential use… To protect the integrity of the sub-district as a hub of high quality jobs and commercial activity, we urge the city to limit the conversions of office buildings into residential buildings.”

In the course of less than 5 years, we’ve seen a complete 180º shift in our needs. Let’s craft zoning rules that are flexible to allow the built environment to adapt.

A rezoning will never please everyone. In order to pass, a rezoning needs a diverse coalition behind it. Which means there’s a lot packed into the policy to try to please everyone. But it’ll never please everyone. Ensure that tweaks are as consistent as possible with the overall purpose of the policy, and approve the policy.

Looking ahead: the Department of City Planning has already stated that the Midtown South plan will include urban design rules that make sure new developments reflect the “existing, beloved loft character of the neighborhood.” I’m all for character, as long as it doesn’t come at the expense of the main goal: evolving from manufacturing space to mixed use buildings.

LPC can get creative to align historic preservation with other goals. In the East Midtown rezoning, one of the newly designated landmarks was right on top of a subway station. The commission added a special “statement of regulatory intent” to the designation, stating that the building’s landmark designation should not impede innovation and evolution of NYC’s transportation system. Consider whether similar creative workarounds might be helpful for facilitating preservation alongside innovation.