Why it’s so expensive to build a public toilet in NYC

New Yorkers have been complaining about toilets since the 90s. Why haven't we fixed this yet? And are the current proposals any good?

Any city will have costs associated with creating a new public bathroom: preparing the site, running new electric and water lines, building the foundation, construction itself, etc.. And it’d be totally reasonable to expect that all of those in NYC would be more expensive than average since our labor costs are higher, and new construction in a dense city is just harder and therefore more expensive.

But there are reasons why New York’s public toilets are uniquely expensive. In ways that are totally avoidable and don’t need to be this way.

We can even compare apples to apples with other cities, using installation of a particular toilet type as our example. The Portland Loo is a no-frills, very joyless, very cheap toilet product designed by the city of Portland (OR).

They’re sold for about $185,000 apiece. The price does not differ depending on the city that’s buying them.

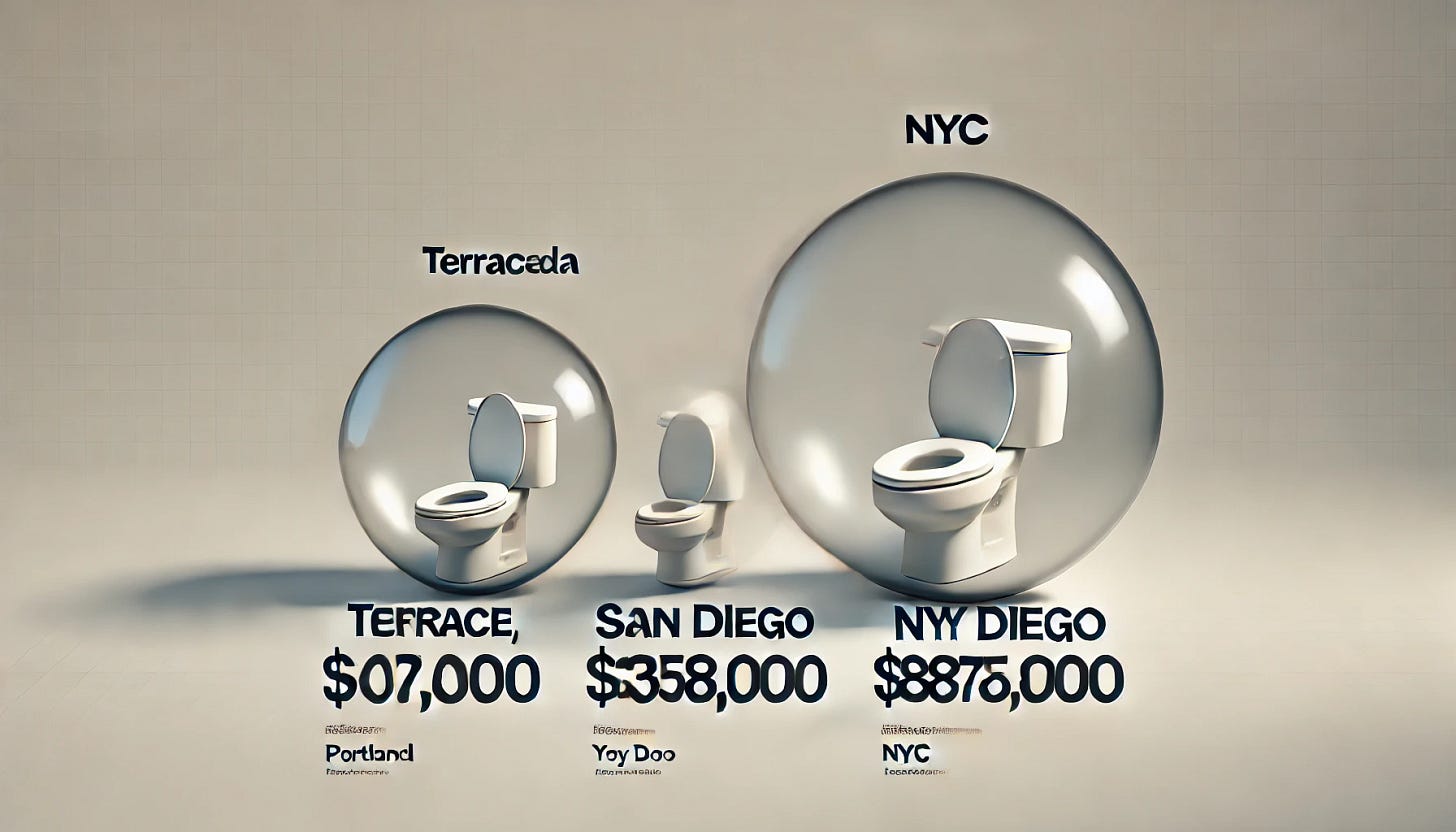

Terrace, Canada spent about $70,000 to install a Portland Loo toilet. San Diego spent about $358,000 to install theirs. NYC is spending $875,000 per toilet.

The first issue is our procurement rules.

If a product is assembled outside of the five boroughs, the facility has to be approved by a special inspector to make sure it complies with city codes and regulations. According to the maker of the Portland Loo: “I built 180 of these, from Portland to Alaska to Miami, and I’ve never had this certification problem. New York City has been the most difficult to have a permit approved for.”

It doesn’t have to be this way.

Why does New York City have such strict building code restrictions on prefabricated construction? This isn’t atypical for blue cities where unions have a ton of power. Local unions want local union employees to have jobs making things. If those things are made elsewhere and brought in, then that decreases local union jobs. Better to make it really difficult to buy premade things from other places. Even if that makes it more expensive for the city to procure things.

The second issue is our self-imposed red tape.

Parks department staff have to shepherd each toilet project through the Public Design Commission, the local community board, and the Landmarks Preservation Commission if the proposed bathroom is in a landmarked area.

I’ve sat through these agency presentations as a community board member. Agency staff put together a very detailed and thorough slide deck, present it at our meeting that starts at 6pm on a weekday, and answer a ton of detailed questions from our group and from the public. The agency always has multiple presenters. Their slides have clearly been through multiple iterations. They’re ready for every question about ADA compliance and whether any historic material will be removed from the area. It takes project management skills, communication skills, patience, and fortitude, to get the required approvals– Parks department staff are full-time well-paid professionals. And this process can take 15 months.

It doesn’t have to be this way.

Why do city departments need to get so many rounds of approval before they can do something simple like installing a toilet? Because neighbors don’t tend to like change. And elected officials like getting re-elected. Without neighborhood buy-in, elected officials can find themselves in hot water with their constituents. You might think: “toilets seem pretty non-controversial.” You’ve never been so wrong. Keep reading.

What have we tried?

In the 90s, NYC tried the coin-operated, self-cleaning toilet kiosk

NYC’s public bathroom problem is not new. Here’s a New York Times headline from 1991: “In New York, Few Public Toilets and Many Rules.”

At the time, NYC’s idea was to try coin-operated, self-cleaning toilet kiosks like the ones that worked so well in London, Paris, and Amsterdam. JCDecaux, which then operated 4,000 of the kiosks across Europe, offered to provide the toilets and maintain them at no cost to New York City in exchange for the right to sell advertising space on them.

After a yearslong negotiation process that even included installation of a pilot toilet and was supposed to result in 30 new public toilets, the program died due to a combination of factors:

The company did not offer a model that was wheelchair friendly. And advocates for the disabled demanded that they be wheelchair accessible.

State law prohibited charging for the use of public toilets. But then the state granted the city an exception to the ban in 1993.

Rules about procurement required opening the project up to bids from other companies besides JCDecaux, thereby drawing out the process by months.

Neighbors were upset about the height of the toilets and neighborhood activists didn’t like the proposal to put ads on them.

Let me add more detail to #4, since I mentioned before that red tape and neighbor opposition go hand-in-hand. At the time, Steve Stollman made a name for himself as the loudest activist voice against the plan– The Times referred to him as “New York's leading toilet gadfly.” Steve even came up with his own codename for his campaign against the public toilet program: “The Privy Council”😂. His biggest beef with the proposal was that there would be advertisements on the toilets that would cover the cost of maintaining them. You might think Steve’s opposition to ads is a very quaint 1998 complaint, but I can attest that unsavory advertising comes up monthly at my community board meetings today.

All of those barriers caused the European kiosk idea to move along at a snail's pace, until Guiliani officially killed it in 1997.

In the 2000s, NYC tried automated public toilets

Bloomberg was the next city leader to try to increase the number of toilets. In 2005, the city signed a contract with a company called Cemusa to install 3,300 bus shelters, 330 newsstands, 37 sheltered bike parking structures, and 20 automated public toilets. The first toilet was installed in Madison Square Park in 2008 and was extremely popular. But the city only ended up installing 5 of the 20 toilets. The other 15 are still in a warehouse in Queens. What were the barriers here?

The city wrote to community boards asking them to propose locations. But many of the sites put forward were not feasible.

Engineering concerns

Neighborhood opposition, including complaints about the bathrooms’ incongruence with neighborhood character (e.g. “The contemporary design is inappropriate in a park that has Victorian stylings.”)

There’s still time to install the warehoused toilets: the city’s contract doesn’t expire till 2026.

In the 2020s, electeds are talking about more public toilets without addressing the core issues

New York City Department of Parks and Recreation (NYC Parks) is making moves on pilots and setting goals:

In 2023, NYC Parks embarked on the Portland Loo pilot that was supposed to have created 5 new bathrooms for around $1M each. Those were supposed to be online last summer, but are still in progress. As of today, the Capital Project Tracker has construction at 35% done and the goal is completion in May 2025. This is a step in the right direction, since Portland Loos are a lower-cost option. But we’re still paying way more than other cities due to our self-imposed red tape and the completion time has dragged out.

In 2024, NYC Parks announced they will create or refurbish 82 public toilets in the next 5 years. This is also a step in the right direction, since the department is committing publicly to a numeric goal. I have no idea if it’s an ambitious goal or not. Since I don’t know what the baseline is for a given year.

So NYC Parks seems to be doing their job with the resources they’ve been allocated and the process they’ve been given. I think. It’s still a little unclear.

But what about the growing demand for more public toilets? Are our elected officials removing barriers to public toilet creation? Are they streamlining red tape? Are they taking a second look at our procurement rules? Mmm no.

As Leah Goodridge noted in her NY Times op-ed last month, electeds are simply proposing to open more public toilets. One bill requires the city to build at least one public restroom for every 2,000 residents by 2035. Another proposes requiring municipal buildings to open their restrooms to the public. Both bills are expected to be voted on by the Council in 2025. But neither of these address the root cause of the issue: the red tape that balloons costs and creates barriers to implementation, and the cost of maintenance. Here’s my guesstimate on maintenance costs again— if the second bill passes, municipal buildings will definitely see their maintenance costs increase.

Here’s our job as citizens:

We can’t ignore costs. We can’t accept that our Portland Loo costs over twice as much as San Diego’s. And we can’t pretend that maintenance costs don’t exist. If we as citizens let our elected officials off the hook for providing basic public services at a reasonable cost, it’s our fault that we don’t have nice things.

We can’t say “no” to bathrooms for being modern-looking or having ads on the sides, if that’s what makes them pencil. If we as citizens won’t settle for anything less than union-made, ad-free, ADA accessible, just-the-right-height bathrooms, it’s our fault that we don’t have nice things.

The funnies

Please enjoy what this press release from the Office of the Mayor did here:

I didn’t make any puns about Flushing in this entire post. Such a missed opportunity.

Please share your best Flushing puns in the comments. And of course any other reflections on this post.🙏🚽

Sachi makes very important points and I very much appreciate her Substack pieces. Two comments that I would like to add:

One. At one time, particularly in the eras before Reagan and Clinton, major municipalities like NYC had any number of people on the payroll who could build things (and fix them as soon as they broke). With the advent of privatization, most municipalities subbed those functions out to vendors and in large part that has led to a great deal of destruction and deterioration of the public space.

Two. The City Charter revision that gave individual residents input opportunities in a the community board or city council districts where they reside was intended to balance, at least in part, the power of wealthy donors with that of the general public. As long as the Supreme Court equates financial donations with free speech (this is likely to be the case for another generation or more), money will hold sway in our two party political system.

Just a postscript: What oil is in Texas, real estate is in NY, these major donors and the high priced strategists, pollsters, lobbyists and consultants only they can afford, are the power players behind all our city, state, and federal electeds.

Thanks Sachi for your work, and for creating this valuable space for civil discourse.

zool

I'm going to refrain from making a comment about Flushing because my parents live there 😅, and honestly, I don’t think I have anything clever to say. But reflecting on this article, I wonder if there has been any attempt at a broader roadmap/project plan/etc. (as opposed to piecemeal efforts) to move us from the current state—which we can all agree isn’t great—to a place that’s at least incrementally better. Even if that means starting with solutions that aren’t fully ADA compliant or rely on ad-subsidized facilities, having a path toward a more ideal vision would be so much better than the status quo. Progress doesn’t have to be perfect from the start, but it has to start somewhere.