Are NYC pensions ready for the next recession?

The current status, potential risks, and decisions that affect City services

In the coming posts, I’ll be sharing the topics I’m exploring to build a stronger foundation for serving on the NYC’s Comptroller transition committee. I’m looking forward to sharing what I learn along the way, so get excited to join me in my research on Comptroller-related topics.

I’m serving on the next NYC Comptroller’s Transition Committee

I’m honored to serve on Mark Levine’s transition committee as he prepares to begin his new role of New York City Comptroller.

One critical function that the Comptroller plays is the role of pension manager. The Comptroller is the investment advisor to the City’s five public pension funds and has a vote on each of the pension boards.

So my first question is: What’s the current status of NYC’s pension funds? Should we be concerned? If there are issues, what are the Comptroller’s levers for possible solutions? This post shares my learnings so far.

First, a very quick primer on NYC pensions

What are these pension plans again? There are 5 NYC pension plans because the one for teachers is separate from the one for policemen, is separate from the one for city employees, and so on. Each one is basically a big pot of money. Teachers contribute to their pot from their paychecks, the City makes contributions, the pot is invested and grows, and the pot pays out retirement checks to retired teachers. Since the pot is really really huge (the 5 pension funds combined equal $294.6 billion ensuring the retirement security of more than 750,000 public servants), the pot is invested in a diverse array of assets, from stocks and bonds to real estate and infrastructure.

It’s SO important that pensions are managed well— for every New Yorker, not just for retirees. The pensions need to have enough money to pay retirees what the City owes them. If the pensions aren’t managed well, and funds are lower than expected, the City still has to pay retirees. That money will just come from other places, which could mean tax increases and cutting city services.

Are NYC pension funds in good shape?

Yes! For now.

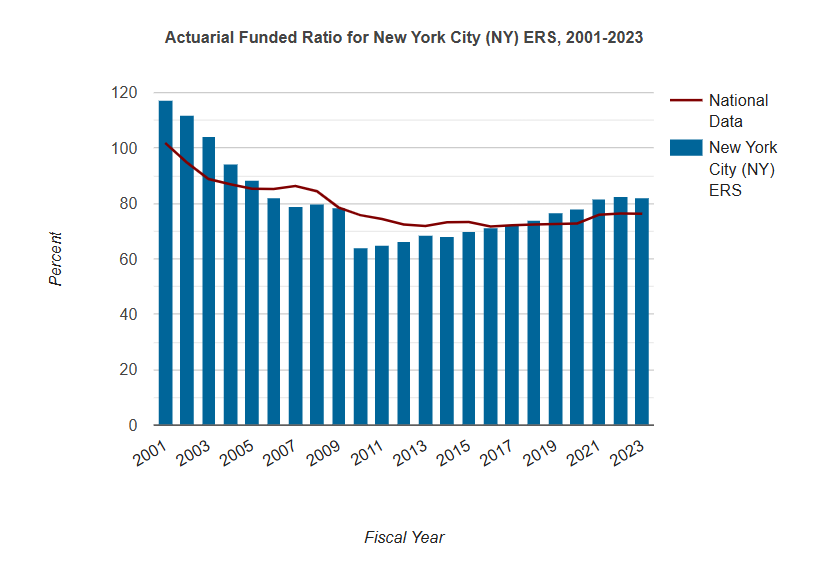

One measure of pension health is the “actuarial funded ratio,” which compares how much money the plan currently has to how much it owes in promised benefits. If the funded ratio is 100%, then the plan is “fully funded”, meaning current assets are enough to pay future benefits. It’s okay for a plan to be at less than 100%, but the goal should always be to get to 100% within a reasonable amount of time.

As of June 2023, the funded ratio for NYC’s combined funds was 83%, which exceeds the average of U.S. public pension plans of 78%. The NYC plans aim to get to 100% funding by 2032.

But the next recession could throw us off course.

The NYC pension funds are in good shape today and have a plan to get to 100% funded. The thing that could throw a wrench in that plan is if there’s a recession anytime between now and 2032, which is likely. Pension assets ebb and flow with the market, so a couple years of recession would throw us off our 100% funded goal significantly.

The stock market is really hot right now– does that mean the City is shoring up reserves to plan for the next recession? No.

You might think that when the market is good, the City would put more into the retirement savings bucket, to shore up for the next recession. Or put more into the City’s reserves (AKA the rainy day fund). That’s not the case. When pension returns are above the 7% target rate set by the State, the extra just goes back to the City budget. At least the extra is phased in over a 5-year time period, so the City can’t spend it all at once.

It’s up to the Mayor and City Council whether they want to use that cash to shore up City reserves. The process would be for them to set aside more rainy days funds in the annual City budget. But politicians don’t tend to be good at saving for hard times. They’d rather spend the money on awesome stuff now that helps them get re-elected.

Just to further illustrate: in 2023, 2024, and 2025, NYC’s pension funds outperformed relative to the goal. For example, in 2025, the pension funds brought in an additional $2 billion over the goal. And yet NYC’s reserves aren’t in a great place. The Citizen’s Budget Commission, a nonpartisan budget research nonprofit, estimates that the City would need $14 billion to cover two years of recession, and yet our current Rainy Day Fund only has $2 billion. So basically: the City isn’t prepared for the next recession, which means likely cuts to City services at that time. The next recession will also probably lead to the City pensions missing their investment goals. When that happens, the City must contribute additional funds to meet pension obligations. Which would lead to additional cuts to City services, on top of the first round of cuts.

Not to mention that the Trump administration has been slashing and burning the federal safety net. NYC and the State have been covering some of those gaps so far, but with the Big Beautiful Bill’s cuts to Medicaid, that’s going to continue to get more expensive. So not only will the next recession bring multiple rounds of cuts to city services, New Yorkers that lose jobs and income won’t have as much federal safety net to rely on either.

Takeaways, reflections, questions

Here’s some questions I’ll be bringing with me going into the transition committee:

Does the extra cash from the pension fund have to go right to the City budget, or are there other workarounds to shore up the pension system in boom years?

Are there other ways the Comptroller’s office can influence how that extra pension cash is used? The Comptroller doesn’t get to vote on the City Budget each year, but the Comptroller does issue a report with recommendations for the budget.

Are there ways the Comptroller’s office can advocate for putting aside money into the rainy day fund while the economy is good?

I’m curious what this post brings up for you— are there other resources you think I should read? Other research questions I should dig into next? Leave me a comment or shoot me an email!

Sachi,

I'd ask for a risk assessment of pension assets in the case of either a 2000 or 2007 bubble bursting. How vulnerable are the assets? And what happens if the returns are say 0% or negative in a year. How does that affect the budget.

$2 bn is woefully inadequate as a rainy day fund. That's less than 2% of expenditures. What are the benchmarks for other large cities and for states?

You raise some excellent questions Sachi!